Re: This thread. http://www.sfmoma.org/pages/research_projects_photography_over

Now, maybe this is my senioritis talking, or maybe it's my frustration with Columbia in general talking, or maybe this is how I've felt all along. My initial response to the question of “is photography over?” would be - “it's not that serious.”

Honestly, I'm not enthralled about how the “legitimacy” of photography SEEMS to have diminished thanks to the digital age and the accessibility of cameras and the massive amount of images just about everywhere, ESPECIALLY the Internet which seems to be a dumping ground of sorts for it all, but, I also know how to move on with my life and keep on making work that is important to me and strive for what my idea of excellence is, photographically. Perhaps my way of thinking and photographing is just really, really simple.

Several commenters on this San Francisco MOMA page say that it depends on what you mean by “photography” and what you mean by “over.” I have to say that I do agree with that, and that it should in fact be specified whether we are talking about commercial and/or fine art photography (or photography that can generate some kind of monetary profit in general) or any kind of image generation from a device with a lens, including cell phone pictures and Facebook snapshots done with point and shoots (which generally do not create any monetary gain...). I am assuming the question “is photography over?” to mean something along the lines of “is art photography, not including all these excessive grainy camera phone pictures and the like, discredited BECAUSE of how accessible photography is now to nearly everyone?”

When people say “photography is over” or “photography is dead,” and talk about all I can think is STOP trying to be a hipster that is just too cool for me, because all you are doing is sounding incredibly whiny. Especially with comments like “it is subject to the product life cycle, which is to say that every new device or process reaches a zenith of popularity only to be superseded by the next invention. The seed of each innovation's demise is thus planted at its birth,” from Jennifer Blessing. This just sounds like it's trying to be way too technical and “smart sounding” for the rest of us who just like to pick up a camera (or the “next invention” of camera, if you must) and shoot and not think so hard about the particular means they are using to create an image and why or why not your chosen device is legitimately considered a camera from one group of people's point of view. I know there is a time for when your

As for who I agree with... I'll start with this one quote Philip-Lorca diCorcia had. “Most predictions [of the future of photography] are based on technical developments that alter the form more than the content. The delivery system is rapidly shifting but the content is little altered.” I feel like this expresses what photography has become extremely well. The devices we use to capture an image have evolved and changed over the years, but some of the outcome is still the same. Obviously we know that image manipulation – however difficult and time consuming it was before Photoshop – existed before digital cameras... I've always been in awe at this image we looked at last week by Oscar Rejlander.

People clearly still do it today, but not in a darkroom, and not with film or glass plates.

Or, let's look at a portrait by Nadar.

|

| Nadar's portrait of Eugene Delacroix |

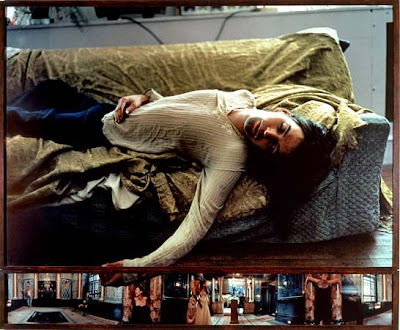

I chose to imitate his style ever so slightly for a European history project final this semester:

Outcome similar, created with different cameras. (Please excuse the hideous watermark, I did it to put them on... Facebook... ugh, how embarrassing. Or not.)

I'm not trying to say that my work in any way compares with Nadar's right now because his portraits are incredible, (and I certainly could have done BETTER at this project) but I am saying that I can get a similar outcome and quality with the way that I shoot and what I shoot with.

Moving on, I agree the most with the first commenter, Vince Aletti. To him, photography being “over” seems “unthinkable” because of how much photography dominates our culture. And, despite “the regular disappearance of favorite photographic papers, the recent dismantling of darkrooms, and the relentless rise of digital capture and output,” old processes seem to always be revived. There has never been only one type of photography and now there are more than ever. He also argues that, if photography is discredited now because digital manipulation takes away from photography's supposed ability to capture truth, then it should have been gone a century ago because photography has never been sheerly about indexicality. Photography has always been used for artistic purposes besides just recording something.

What IS over, according to Aletti, is “the narrow view of photography — the idea that the camera is a recording device, not a creative tool, and that its product is strictly representational — not manipulated, not fabricated, not abstract.” I certainly agree with this as well.

Clearly there are still artists today who do darkroom work and/or use alternative processes, like Robert and Shana Parkeharrison.

So that certainly isn't entirely dead, just waning for now, perhaps. Maybe someday in the far off distant future those processes may not exist anymore due to no more materials, but there will still be means of taking photographs.

I do think that anyone who says photography is strictly darkroom, and strictly representational really does have a narrow view of what photography is or always has been. That is to discredit every renown photographer who has made work that was not entirely straightforward and was even the least bit imaginative.

I still feel like I am arguing the same point I made several weeks ago about this. If I alter or manipulate an image in Photoshop, it has the same effect as if I were to do it in the darkroom, except much easier on my terrible eyesight. I feel like this is such a merry go round of an argument and that I am just constantly repeating myself. It is not really an argument that can be won. It reminds me of when I go out and talk about Jesus on the streets of hipster neighborhoods here and nobody wants to hear about it because "we all have our own beliefs." Doesn't just about everything in this world eventually get “beaten to death” to the point where it seems like it's “over” because it's been done so much? One commenter said “God is over” to make his point, even. (Though I have to disagree with that particular statement entirely..) It is just the point that most art is done so much that it all eventually becomes old to us no matter the process. I remember my senior year of high school being in art class, and that same teacher taught AP art (the “honors” version that took two class periods instead of one) and all of a sudden everyone in AP art was doing “drip” paintings because it just looked like the cool thing to do. My teacher became irritated and forced all those students to actually do research on its origin and who the artists were who came before them who created that kind of work. Maybe he would even have gone as far as to say, “that style of painting is over.” What isn't over by now, if you put it that way?